Donatello has depicted St. Mary Magdalene (1440’s) as a haggard, thin figure. It was thought that she lived as a prostitute before turning to a life of penance, isolating herself in the wilderness. Her ankle length hair acts as a garment to cover her naked body. Typically, she was portrayed by artists as beautiful, and it was uncommon to see Magdalene represented at a later point in her life. The Magdalene is currently housed in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence very near to where Donatello would have created it.

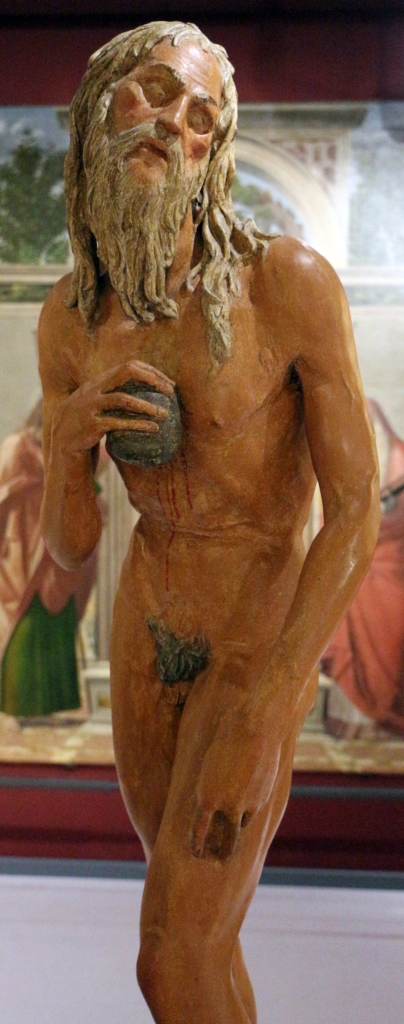

Donatello, St Jerome, 1386-1466, 147cm, The Frick Collection, New York.

Photographed By Una D’Elia

Creating the Forms

Wood as a sculptural material was historically chosen to depict Magdalene. Donatello’s Magdalene was carved out of a single trunk of white poplar. This material was challenging to carve because of its tendency to chip. To avoid cracking caused by changes in humidity, fifteenth-century sculptures were typically hollowed. However, Donatello did not hollow out his wooden figures. Plaster was added on top of the wood to serve as a ground for paint. Donatello also sculpted her long tendrils of hair in plaster. This was an unconventional use of plaster because its viscous consistency would have made it difficult to model, as opposed to a more malleable and firm material such as clay. Scans show that in Donatello’s St. Jerome (1386-1466), plaster was applied layer upon layer to achieve volume in the hair and fine details. Once each layer had dried, another would be applied. It is a curious decision to model in this way because when wet plaster comes in contact with dry plaster, the dry plaster absorbs all of the water and it dries instantly upon contact, which would make modelling more difficult. Donatello was not afraid to stray from tradition and experiment with materials.

Colour and Gold

After the plaster was modelled on the wood, paint was applied. Magdalene’s surface is entirely polychromed in a warm tan brown colour which was made from red ochre, vermillion and lead white pigments. The gold would have been applied last. The thin gold highlights that extend from her roots to the very bottom ends of her hair enhance its volume and dimension. To achieve this effect, gold was ground into a very fine powder and mixed with a binding agent to create consistent gold compound that was painted smoothly overtop of the brown tempera paint.

Digital Map: Materials Near and Far

This digital map is a visual representation of the amount of work put into the actual mining, grinding and production, and distances travelled to acquire the desired sculptural materials. Pigments for Magdalene were sourced as near as Siena and as far as Turkey, while the gold may have come all the way from North Africa. Each point on the map indicates a specific material that has been traced to these locations as accurately as possible.

Cadium Red, Photographed by Maddi Andrews

Carbon Black, Photographed by Maddi Andrews

Lead White, Photographed by Maddi Andrews

Breanna Gordon, Queens University

Bibliography: Strom, Deborah Phyl. STUDIES IN QUATTROCENTO TUSCAN WOODEN SCULPTURE. Order No. 7919319, Princeton University, 1979. Thompson, Daniel V. The Materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting. New York: Dover Publications, 1998. Belozerskaya, Marina. Luxury Arts of the Renaissance. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2005. Kirby, Jo, Susie Nash, Joanna Cannon, and Susanne Kubersky-Piredada. Trade in Artists Materials: Markets and Commerce in Europe to 1700. London: Archetype Publications, 2010. Harris, Jim. Donatello’s Polychrome Sculpture: Case Studies in Material and Meaning. Vol. 1. London: The Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 2010. Schulz, Anne Markham. Woodcarving and Woodcarvers in Venice, 1350-1550. Centro Di, 2011. Anderson, Christy, et al. The Matter of Art: Materials, Practices, Cultural Logics, C.1250-1750. Manchester University Press, 2016. Ng, Aimee, Alexander J. Noelle, and Xavier F. Salomon. Bertoldo Di Giovanni: the Renaissance of Sculpture in Medici Florence. New York: The Frick Collection, 2019. D’Elia, Una. St. Mary Magdalene, Donatello, Renaissance Polychrome Sculpture in Tuscany. Accessed December 5, 2019. https://qspace.library.queensu.ca/handle/1974/24686. D’Elia, Una. Reconstructing Renaissance, The Colours of Italian Renaissance Sculpture; Red. coloursofsculpture.art.blog, March 22, 2019. Accessed December 14th, 2019.